Functions

Functions are the main building blocks in Julia. Every operation on variables and other elements is performed through functions, even the mathematical operators that we have seen in the chapter before are functions in an infix form.

If we want to simplify what a function is, we can picture it as a box which can optionally take an input, performs some operations and returns an output of some sort.

Defining functions

A typical function looks like this:

function plus_two(x)

#perform some operations

return x + 2

end

A function starts with the word function and ends with end.

Please notice the indentation of the body of the function (lines 2 and 3): the body of a function (and many other constructs in Julia) must be indented. Although the number of indentation spaces is not strictly fixed, it is a conventional rule to indent by four spaces.

In Julia the indentation rules are not as strict as in Python, nonetheless it is recommended that you don’t mix tabs and spaces while indenting you code, and tabs are usually discouraged as they may lead to problems when switching from one operating system to another.

Please notice that every “block” of code ends with an end, this way you can always know when something starts and ends.

Although this is the most common way to write functions, it is sometimes convenient to use the inline version:

plus_two(x) = x+2

It is also possible to create anonymous functions (like lambdas in Python) using the following structure:

plus_two = x -> x+2

It is not recommended to use anonymous functions unless they are really simple. It is generally better to write functions in the first or second way unless you need to write a small wrapper around another function and pass it to a third function.

The following example is a bit more advanced and it includes topics which we have not yet studied, like integrals and how to install and use an external package. You can always come back later to read this example as it is not fundamental at this point of the course but you may find it useful one day. The take home message is never use anonymous functions unless you know what you are doing.

More on anonymous functions

For example, let’s consider a function f of three variables x, y and z. Let’s suppose we want to fix two variables (y and z) and integrate f over x, we could do it with:

using Pkg

Pkg.add("QuadGK")

using QuadGK

f(x,y,z) = (x^2 + 2y)*z

quadgk(x->f(x,42,4), 3, 4)

but we could have also written:

using Pkg

Pkg.add("QuadGK")

using QuadGK

f(x,y,z) = (x^2 + 2y)*z

arg(x) = f(x,42,4)

quadgk(arg, 3, 4)

and the result would have been the same, furthermore, in my opinion, the latter is a cleaner way to write integrals, especially if we wrap everything inside another function:

f(x,y,z) = (x^2 + 2y)*z

function integral_of_f(y,z)

arg(x) = f(x,y,z)

result = quadgk(arg, 3, 4)

return result

end

Functions can be defined inside other functions, which is really useful to make the code more readable. Avoid writing long functions inside other functions, but use small lightweight functions if needed (think of them as if they were aliases to make the code more readable and simple to maintain). When we define a function inside another function, we can use simpler and shorter names (like arg or f) without the risk of having overlapping functions and unexpected behaviour.

Void functions

Functions may also take no arguments and return no value, if needed, for example we can create a function which prints a string:

function say_hi()

println("Hello from TechyTok!")

return

end

If the function returns no value the return can be omitted. In general it is also possible to omit the return statement even in regular functions and Julia will return the last computed value. However, in my opinion, in this case it is better to return explicitly a value, for clarity’s sake.

Optional positional arguments

Sometimes a parameter may have a default value which can be specified so that the user doesn’t need to always type it. For example let’s write a function which converts our “weight” as measured on Earth (in kg) to the one measured on another planet.

function myWeight(weightOnEarth, g=9.81)

return weightOnEarth*g/9.81

end

If the user types myWeight(60) and doesn’t specify g, he or she will get his/her weight as measured on Earth:

>>>myWeight(60)

60

If I specify the gravitational acceleration g on another planet (let’s say Mars)

>>>myWeight(60, 3.72) # https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravity_of_Mars

22.75

I get my weight on Mars! Pretty light, isn’t it?

As the name suggests positional arguments must be used in the right order, we cannot specify g before weightOnEarth and, as opposed to other languages like Python, in Julia we cannot change the order of the arguments even if we specify the name of the parameter. If we want optional arguments with no fixed position, we need to use keyword arguments.

Keyword arguments

Let’s say we have a function which takes many optional parameters, it might become cumbersome for the user to remember the right order. That’s the case where keyword arguments come in handy!

Keyword arguments are separated from positional arguments by a semicolon ; and must always be addressed by their name, although their order is irrelevant. They can be either optional and not, but usually we use keyword arguments for optional parameters.

function my_long_function(a, b=2; c, d=3)

return a + b + c + d

end

Here a and b are positional arguments, while c and d are keyword arguments.

>>>my_long_function(1, c=3)

9

>>>my_long_function(1, 2, c=3)

9

>>>my_long_function(1, 2, d=5, c=3)

11

>>>my_long_function(1, 2, d=5)

ERROR: UndefKeywordError: keyword argument c not assigned

As you can see, even if c is a keyword argument, it must always be specified!

Performance tip

It is preferable to use positional arguments whenever high performance is required (for example when writing functions which need to be called many times), it is always possible to write a wrapper to a function (or a method of the function) which uses keyword arguments, if needed, as we will see later on when we deal with multiple dispatch.

Function documentation

It is possible to get information on a function by typing in the REPL ? functionName, this will fetch the documentation for that function, if available, or it will print some information which the compiler is able to infer.

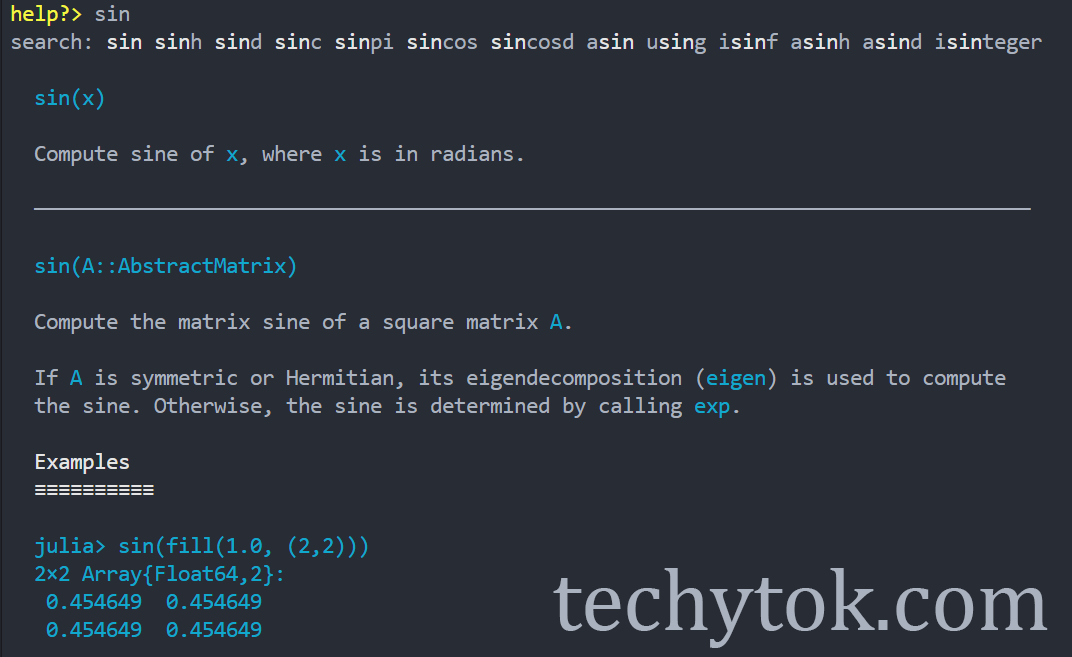

For example if we query the documentation of the sin function with ? sin we get this output:

It is also possible to write the documentation of your functions in the following way:

"""

Description of the function

"""

function foo(x)

#... function implementation

end

You can find more information on how to write the code documentation in the lesson on modules and at the official documentation.

Conclusions

In this lesson we learned how to define functions and use positional as well as keyword arguments.

If you liked this lesson and you would like to receive further updates on what is being published on this website, I encourage you to subscribe to the newsletter! If you have any question or suggestion, please post them in the discussion below!

Thank you for reading this lesson and see you soon on TechyTok!

Leave a comment