Modules

In this lesson we will learn what modules are and how they can be used for code reusability.

You can find the code snippets from this lesson here.

Working with modules

Libraries in Julia come in the form of module which can be loaded via the using notation. A module is a separate environment with its sets of variables and functions, some of which are exported in the calling scope, which means that you can call exported functions by simply typing their name as if they where defined in the same scope, while others are accessible only through the ModuleName.functionName notation.

In order to use an existing official module, we need first to install it and then import it, you can do it using the package manager. For this example we will use the Special Functions package, which contains functions such as the gamma function and the Bessel functions.

using Pkg

Pkg.add("SpecialFunctions")

At line 1 we import the module called Pkg (with the using keyword) and at line 2 we call the add function which is defined inside it. add takes as its argument the name of the package which we want to install and it will download and build it for us. When it is done (it may take a few minutes) we are ready to use the functions available inside the package!

using SpecialFunctions

>>>gamma(3)

2.00

>>>sinint(5) #sine integral

1.5499312449446743

If we don’t want to import all of the functions available inside SpecialFunctions but only some of them, for example the gamma function and sinint, but not cosint, we can do it in the following way.

Make sure to restart the REPL first, once a package is installed you don’t need to run Pkg.add... anymore!

using SpecialFunctions: gamma, sinint

>>>gamma(3)

2.00

>>>sinint(5)

1.5499312449446743

>>>cosint(5)

UndefVarError: cosint not defined

Sometimes it is useful to call a function taking in consideration the package where it is defined. If a function is not exported by the module (more on export later) or if there are several modules which export a function with the same name and same argument signature, we can specify which module the function belongs to using the following syntax:

function gamma(x)

println("I am another 'gamma' function")

return x^2

end

>>>using SpecialFunctions

WARNING: using SpecialFunctions.gamma in module Main conflicts with an existing identifier.

>>>gamma(3)

I am another 'gamma' function

9

>>>SpecialFunctions.gamma(3)

2.0

As you can see at line 7, a warning is shown to let us know that the gamma function exported by SpecialFunctions is in conflict with the gamma function which we have defined at line 1.

At line 9 we call the gamma function and as we can see the first definition of the function is what is used (i.e. the user defined function), if we want to call the gamma function inside SpecialFunctions we need to specify the module which contains it (as done on line 13).

In the case where a conflict like this may arise, it is better to avoid the using notations and instead use import, which “imports” the desired module all the same but without exporting any function in the calling scope.

import SpecialFunctions

>>>gamma(3)

UndefVarError: gamma not defined

>>>SpecialFunctions.gamma(3)

2.0

function gamma(x)

println("I am another 'gamma' function")

return x^2

end

>>>gamma(3)

I am another 'gamma' function

9

At line 4 we see that gamma is not defined if we simply type import SpecialFunctions and at line 6 we see that it becomes mandatory to call it using SpecialFunctions.gamma(3), after we define the gamma function at line 9-12 it becomes possible to call our “custom” gamma function.

User defined modules

It is possible to think of modules as compact blocks of variables and functions which can be easily imported in another program. One should not think of a module as something similar to what is a class in object oriented languages such as C++ and Python, but instead as a separate global scope with its own set of variables and functions which can be called from another program. One difference with a class is that it is not possible to import a module several times to have different sets of “global variables”, while it is usual in OOP languages to have different instances of the same class.

In Julia the functions inside a module should thus depend only on their input (and eventually some global variables or other functions defined inside the module which will be shared). We will see in the next lesson how all the data which should be passed to a function and which has to be eventually modified by the function can be conveniently wrapped into a structure. As an anticipation, what may look like object.foo(x) in Python/C++, in Julia will look like foo(x, dataStructure). Although it may seem a trivial difference, we will see that this difference is at the base of multiple dispatch, which is one of the main strength of Julia!

In the following example we will define a simple module which performs some operations and exports a function .

module MyModule

export func2

a=42

function func1(x)

return x^2

end

function func2(x)

return func1(x) + a

end

end #end of module

#%%

using .MyModule

>>>func2(3)

51

>>>func1(3)

UndefVarError: func1 not defined

>>>MyModule.func1(3)

9

A module starts with the module keyword and should end with end. Contrarily to functions and other blocks, one should not add indentation to a module block.

We define a variable, a, and two functions, func1 and func2, but we export only func2 (see line 2), which means that only func2 will be accessible in the outer scope if we don’t specify the module to which it belongs.

At line 17 we import MyModule, notice the . before the module name, this is needed as MyModule is not an “official” package and ultimately because MyModule is defined in the Main scope (the .Name notation is an abbreviation of Main.Name). At line 19 we call func2 and at line 22 func1, notice that an error is thrown when we call func1 as it is not exported. If we want to access it we need to type MyModule.func1(3) as shown at line 25.

Code inclusion

As modules become bigger and longer, it is a good practice to split code among different files. In Julia it is simple to include code from another file in the current program as if the code were written inside the same file through the include() function.

include() takes as its argument the name of the file which should be “pasted” inside the current program, pay attention to its location as you may need to write the path to the file.

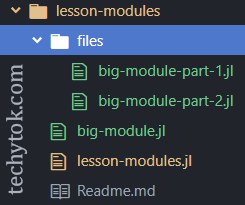

For this example let’s create three files as shown in the picture:

The content of big-module-part-1.jl should be:

function func1big(x)

return x^2

end

The content of big-module-part-2.jl should be:

a = 42

function func2big(x)

return func1big(x) + a

end

And the content of big-module.jl should be:

module MyBigModule

include("files/big-module-part-1.jl")

include("files/big-module-part-2.jl")

export func2big

end #end of module

We can now import MyBigModule inside our program (lesson-modules.jl) in the following way:

include("big-module.jl")

using .MyBigModule

>>>func2big(3)

51

Depending on your folder structure and if you have downloaded/cloned the techytok-examples repository, you may need to change the current working directory to the one which contains the files described above (in my case “lesson-modules”) using the command cd("lesson-modules") for this example to work.

Although one should give meaningful names to the files which make up a module (and not part1, part2, etc.) this was an example of how one can structure a module:

- make a main “module file” which contains the module, imports all of the other files using

includeand exports the desired functions. - make several files with meaningful names which perform a group of operations with a common topic.

This structure lets you easily extend the module (simply add new files) and makes the code more maintainable, if functions which perform similar tasks are grouped in the same file.

Notice that in Julia it is not important the order in which you include the files in the main module, but in my opinion it is a good practice to include the files in a sort of chronological order. In our example the function func2big depends on func1big which is defined inside big-module-part-1.jl, so we should import it before we includebig-module-part-2.jl.

Remember that when we call include() the code gets “pasted” inside the file where include is called, so it is not necessary to call include inside big-module-part-2.jl as the compiler will see part1, part2 and the main module as a unique file (furthermore, using include inside a file which gets included by another file may lead to errors).

Code reusability

The goal of a module is to write a set of functions, define a series of variables or types which can be easily reused in other programs (your other programs for example), so one should give meaningful names to the functions (not like func1 and func2) and make them as general and stand-alone as possible.

Since you will likely come back to a module you have written once every few months, you may not remember what a specific function does: it is thus a good idea to add annotations to your code through # comment and write a small description of the function.

When you type ? functionName in the REPL you get a description of that function and usually an example of how it can be used. We will now learn how to write such description for our functions.

Code documentation

One can write the description of a function in the following way:

"""

Description of the function

"""

function foo(x)

#... function implementation

end

There is a set of rules for writing documentation listed in the official documentation. Here is a summary:

- Start with the function signature (i.e. function name and arguments) indented by 4 spaces

- Write a small summary of what the function does

- If necessary explain what the arguments mean/do

- Optionally give an example of usage of the function

It is advisable to prepend @doc raw"""..., in this way you will be able to write markdown code inside the description string without the need to escape special characters.

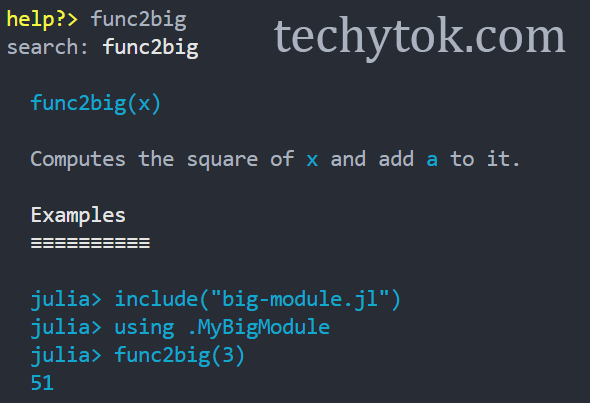

Let’s see how we can document, for example, func2big:

@doc raw"""

func2big(x)

Computes the square of `x` and add `a` to it.

# Examples

```julia-repl

julia> include("big-module.jl")

julia> using .MyBigModule

julia> func2big(3)

51

```

"""

function func2big(x)

return func1big(x) + a

end

After we have imported MyBigModule we can type ? func2big in the REPL to read the documentation:

Or, if you are using the Juno IDE, we can look up the documentation for func2big in the documentation explorer (the documentation explorer may take a few minutes to compile the documentation the first time you use it):

Pretty neat, don’t you think?

It is good practice to write the documentation with at least the function signature and a short description for each function you define: this will make navigating through the code much easier and you can keep open the documentation tab in Juno to look for the signature (i.e. the arguments) of a specific function you wrote.

Conclusions

We have learned how to import an existing “official” module and how to write our own. We have learned how it is possible to split a piece of code between multiple files and how code reusability can be improved by module usage. Finally, we have learned how to write proper code documentation in order to make it easier to find out and remember what a function does.

If you liked this lesson and you would like to receive further updates on what is being published on this website, I encourage you to subscribe to the newsletter! If you have any question or suggestion, please post them in the discussion below!

Thank you for reading this lesson and see you soon on TechyTok!

Leave a comment