Types and Structures

In this lesson we will learn what types are and how it is possible to define functions that work on types. We will learn which are the differences between abstract and concrete types, how to define immutable and mutable types and how to create a type constructor. We will give a brief introduction to multiple dispatch and see how types have a role in it.

You can find the code for this lesson here.

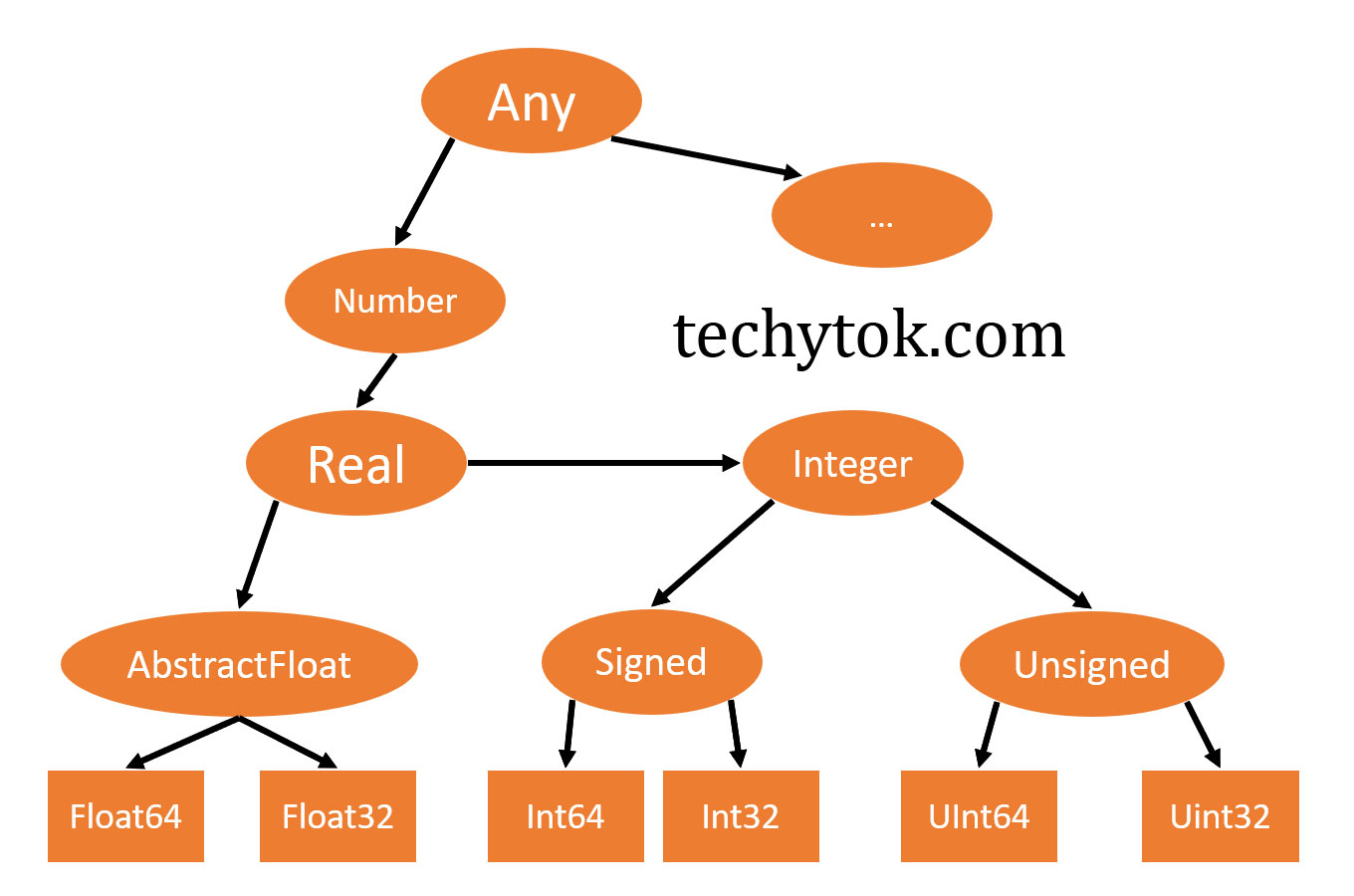

We can think of types as containers for data only. Moreover, it is possible to define a type hierarchy so that functions that work for parent type work also for the children (if they are written properly). A parent type can only be an AbstractType (like Number), while a child can be both an abstract or concrete type.

In the tree diagram, types in round bubbles are abstract types, while the ones in square bubbles are concrete types.

Implementation

To declare a Type we use either the type or struct keyword.

To declare an abstract type we use:

abstract type Person

end

abstract type Musician <: Person

end

You may find it surprising, but apparently musicians are people, so Musician is a sub-type of Person. There are many kind of musicians, for example rock-stars and classic musicians, so we define two new concrete types (in particular this kind of type is called a composite type):

mutable struct Rockstar <: Musician

name::String

instrument::String

bandName::String

headbandColor::String

instrumentsPlayed::Int

end

struct ClassicMusician <: Musician

name::String

instrument::String

end

Notably rock-stars love to change the colour of their headband, so we have made Rockstar a mutable struct, which is a concrete type whose elements value can be modified. On the contrary, classic musicians are known for their everlasting love for their instrument, which will never change, so we have made ClassicMusician an immutable concrete type.

We can define another sub-type of Person, Physicist, as I am a physicist and I was getting envious of rock-stars:

mutable struct Physicist <: Person

name::String

sleepHours::Float64

favouriteLanguage::String

end

aure = Physicist("Aurelio", 6, "Julia")

>>>aure.name

Aurelio

>>>aure.sleepHours

6

>>>aure.favouriteLanguage

"Julia"

Luckily my exam session is over now and I finally have a little bit more time to sleep, so I’ll adjust my sleeping schedule to sleep eight hours:

aure.sleepHours = 8

Incidentally I am also a ClassicMusician and I play violin, so I can create a new structure:

aure_musician = ClassicMusician("Aurelio", "Violin")

>>>aure_musician.instrument = "Cello"

setfield! immutable struct of type ClassicMusician cannot be changed

As you can see, I love violin and I just can’t change my instrument, as ClassicMusician is an immutable struct.

I am not a rock-star, but my friend Ricky is one, so we’ll define:

ricky = Rockstar("Riccardo", "Voice", "Black Lotus", "red", 2)

>>>ricky.headbandColor

red

Functions and types: multiple dispatch

It is possible to write functions that operate on both abstract and concrete types. For example, every person is likely to have a name, so we can define the following function:

function introduceMe(person::Person)

println("Hello, my name is $(person.name).")

end

>>>introduceMe(aure)

Hello, my name is Aurelio

While only musicians play instruments, so we can define the following function:

function introduceMe(person::Musician)

println("Hello, my name is $(person.name) and I play $(person.instrument).")

end

>>>introduceMe(aure_musician)

Hello, my name is Aurelio and I play Violin

and for a rock-star we can write:

function introduceMe(person::Rockstar)

if person.instrument == "Voice"

println("Hello, my name is $(person.name) and I sing.")

else

println("Hello, my name is $(person.name) and I play $(person.instrument).")

end

println("My band name is $(person.bandName) and my favourite headband colour is $(person.headbandColor)!")

end

The ::SomeType notation indicates to Julia that person has to be of the aforementioned type or a sub-type. Only the most strict type requirement is considered (which is the lowest type in the type tree), for example ricky is a Person, but “more importantly” he is a Rockstar (Rockstar is placed lower in the type tree), thus introduceMe(person::Rockstar) is called. In other words, the function with the closest type signature will be called.

This is an example of multiple dispatch, which means that we have written a single function with different methods depending on the type of the variable. We will come back again to multiple dispatch in this lesson, as it is one of the most important features of Julia and is considered a more advanced topic, together with type annotations. As an anticipation ::Rockstar is a type annotation, the compiler will check if person is a Rockstar (or a sub-type of it) and if that is true it will execute the function.

Type constructor

When a type is applied like a function it is called a constructor. When we created the previous types, two constructors were generated automatically (these are called default constructors). One accepts any arguments and calls convert to convert them to the types of the fields, and the other accepts arguments that match the field types exactly (String and String in the case of ClassicMusician). The reason both of these are generated is that this makes it easier to add new definitions without inadvertently replacing a default constructor.

Sometimes it is more convenient to create custom constructor, so that it is possible to assign default values to certain variables, or perform some initial computations.

mutable struct MyData

x::Float64

x2::Float64

y::Float64

z::Float64

function MyData(x::Float64, y::Float64)

x2=x^2

z = sin(x2+y)

new(x, x2, y, z)

end

end

>>>MyData(2.0, 3.0)

MyData(2.0, 4.0, 3.0, 0.6569865987187891)

Sometimes it may be useful to use other types for x, x2 and y, so it is possible to use parametric types (i.e. types that accept type information at construction time):

mutable struct MyData2{T<:Real}

x::T

x2::T

y::T

z::Float64

function MyData2{T}(x::T, y::T) where {T<:Real}

x2=x^2

z = sin(x2+y)

new(x, x2, y, z)

end

end

>>>MyData2{Float64}(2.0,3.0)

MyData2{Float64}(2.0, 4.0, 3.0, 0.6569865987187891)

>>>MyData2{Int}(2,3)

MyData2{Int64}(2, 4, 3, 0.6569865987187891)

It is crucial for performance that you use concrete types inside a composite type (like Float64 or Int instead of Real, which is an abstract type), thus parametric types are a good option to maintain type flexibility while also defining all the types of the variables inside a composite type.

For more information on constructors see this article.

Example

Mutable types are particularly useful when it comes to storing data that needs to be shared between some functions inside a module. It is not uncommon to define custom types in a module to store all the data which needs to be shared between functions and which is not constant.

module TestModuleTypes

export Circle, computePerimeter, computeArea, printCircleEquation

mutable struct Circle{T<:Real}

radius::T

perimeter::Float64

area::Float64

function Circle{T}(radius::T) where T<:Real

# we initialize perimeter and area to -1.0, which is not a possible value

new(radius, -1.0, -1.0)

end

end

@doc raw"""

computePerimeter(circle::Circle)

Compute the perimeter of `circle` and store the value.

"""

function computePerimeter(circle::Circle)

circle.perimeter = 2*π*circle.radius

return circle.perimeter

end

@doc raw"""

computeArea(circle::Circle)

Compute the area of `circle` and store the value.

"""

function computeArea(circle::Circle)

circle.area = π*circle.radius^2

return circle.area

end

@doc raw"""

printCircleEquation(xc::Real, yc::Real, circle::Circle )

Print the equation of a cricle with center at (xc, yc) and radius given by circle.

"""

function printCircleEquation(xc::Real, yc::Real, circle::Circle )

println("(x - $xc)^2 + (y - $yc)^2 = $(circle.radius^2)")

return

end

end # end module

#%%

using .TestModuleTypes

circle1 = Circle{Float64}(5.0)

computePerimeter(circle1)

circle1.perimeter

computeArea(circle1)

circle1.area

printCircleEquation(2, 3, circle1)

This is a simple module which implements a Circle type which contains the radius, perimeter and area of the circle. There are three functions which respectively compute the perimeter and area of the circle and store them inside theCircle structure. The third function prints the equation of a circle with a given centre and the radius stored inside a Circle structure.

Notice that we could have simply computed the perimeter and area inside the type constructor, but I have chosen not to do so for educative purposes.

Conclusions

This lesson has been a little bit more conceptually difficult than the previous ones, but you don’t need to remember everything right now! We will use types in the future lessons, so you will naturally get accustomed to how they works over time.

We have learnt how to define abstract and concrete types, and how to define mutable and immutable structures. We have then learnt how it is possible to define functions that work on custom types and we have introduced multiple dispatch. Furthermore, we have seen how to define an inner constructor, to aid the user create an instance of a composite type. Lastly, we have seen an example of a module which uses a custom type (Circle) to perform and store some specific computations.

If you liked this lesson and you would like to receive further updates on what is being published on this website, I encourage you to subscribe to the newsletter! If you have any question or suggestion, please post them in the discussion below!

Thank you for reading this lesson and see you soon on TechyTok!

Leave a comment